Inuit Knowledge

Inuit History and Lifeways

The Inuit, the principal circumpolar people of North America and Greenland, and their Thule ancestors, have occupied the pan-Arctic region for more than 700 years.

The Arrival of Thule Culture

Around the 13th century A.D. the Thule people, the ancestors of today’s Inuit, began to spread eastward from Alaska. Within two centuries, they had established themselves across the entire North American Arctic region, including Greenland.

The Thule accomplished this remarkably rapid migration because they were a culture oriented to travel and mobility.

Thule Technology

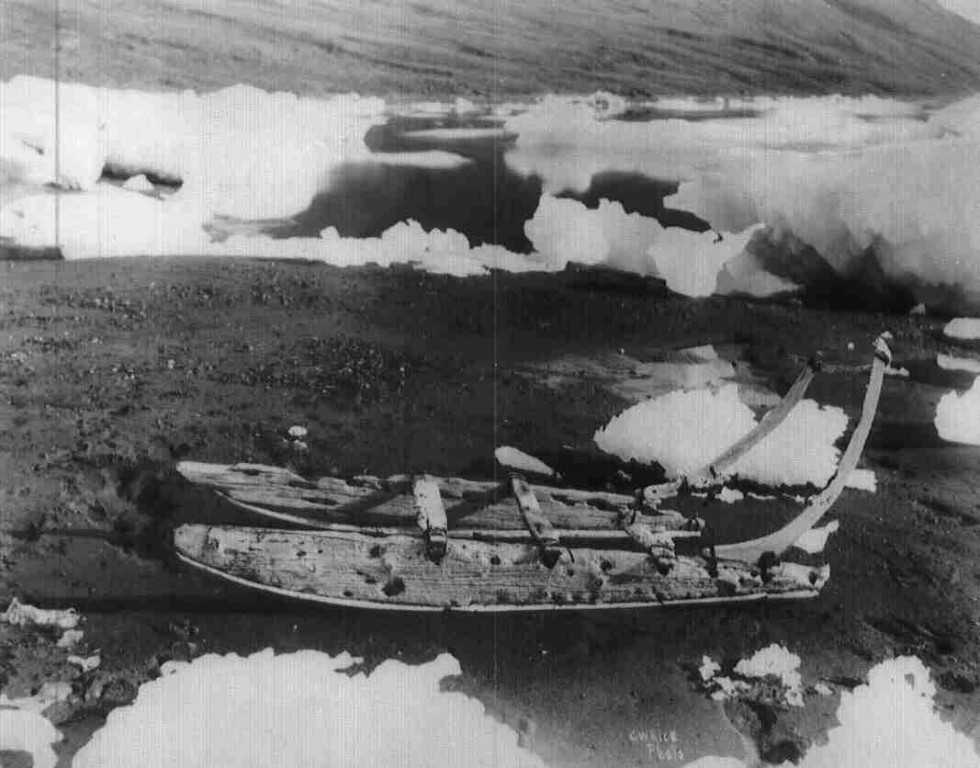

When they left Alaska, they had already developed a highly sophisticated culture with everything they needed for long journeys across the Arctic. This included:

- a wide array of portable tools, including sophisticated hunting and fishing tools

- weapons for hunting at sea and on land

- materials for clothing

- tent coverings

- sleeping bags that could be readily transported on sledges or skin boats

- two types of boat – kayaks and umiaks

- sleds and the use of dogs for motive power

Adaptation and Survival in the Arctic

For all indigenous peoples in the Arctic, the key to survival was often their capacity to adapt to new and changing natural environments, and more generally their adaptability as a culture.

For peoples largely reliant on hunting and gathering, successful occupation required adaptations to the natural ecology and adjusting to its frequent and unpredictable adversities.

All indigenous groups of the High Arctic, in every era, were nomadic. They moved the entire community and its belongings over extended distances.

Inuit needed to develop strategies of resource use closely attuned to the resource base of a region, its seasonal cycle, feeding and migratory patterns of its major game animals.

They also needed to develop flexible forms of social organization oriented to hunting, flexibility, and the practice of limiting their bands to small-sized groups that could more readily adapt to changing conditions.

When Greenland Inughuit accompanied Peary to Fort Conger during his 1898-1902 North Pole expedition they reoccupied and overwintered in the far northern regions that they apparently had not visited for as long as two centuries. The probable reason for the hiatus in occupation was the climatic cooling episode known as the Little Ice Age that curtailed opportunities to secure game and survive in this very remote region.

As the climate cooled, Inuit families living in northern Ellesmere Island and adjacent areas of the far north retreated to the Smith Sound region on both the east-central coast of Ellesmere and the north-western coast of Greenland across the channel.

That region borders the North Water, the largest polynia in the world. A polynia is a unique formation of water and circulating ice floes surrounded by pack ice that remains open even in the winter.

Both historically and today Inuit have relied on polynias to hunt in the dark cold winters, enabling their success in this challenging environment.

After arriving at Fort Conger in early 1899, Inughuit members of Peary’s party quickly adapted to the geography and resource base of the region.

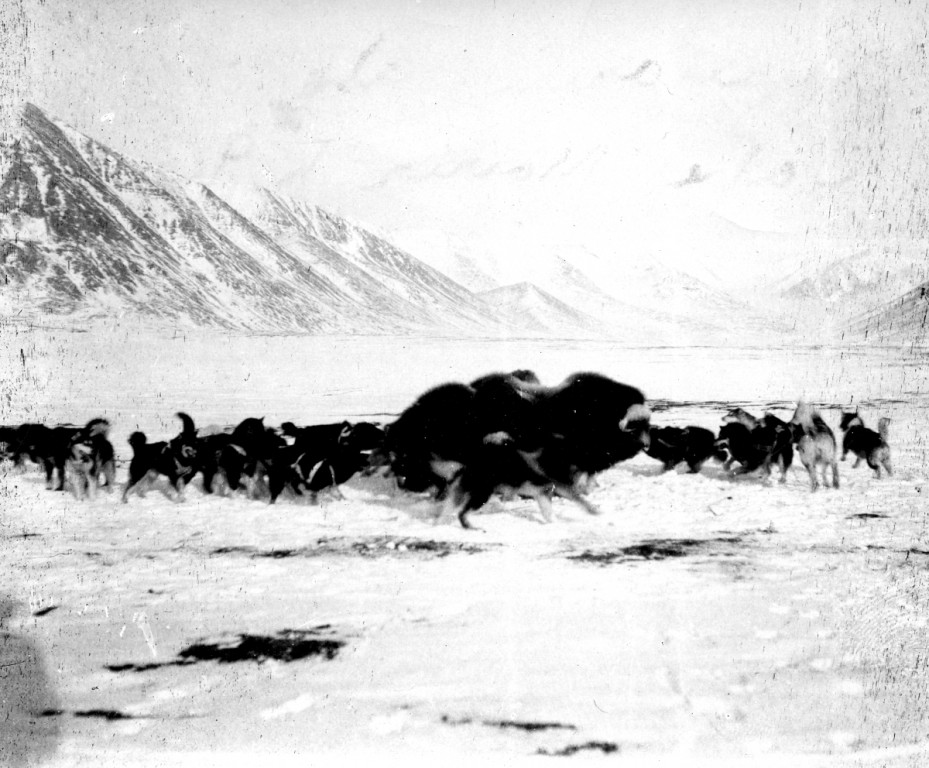

They located areas of important habitat for muskoxen on the Hazen plateau in the interior, as well as opportunities to harvest char in the Ruggles River, Lake Hazen, and a series of small lakes to the east of this major lake.

During the brief period of open water in the late summer, they also caught seals while hunting from kayaks in Discovery Harbor and adjacent waters.

On these forays, Inughuit women resumed their long-standing roles in preparing and stretching animal skins, sewing warm fur garments, and making sleeping bags and tents from skins.

During Peary’s last two North Pole expeditions of 1905-06 and 1908-09, when based at Cape Sheridan on Ellesmere’s northeast coast, a large Inughuit party again accompanied him. They continued to rely upon the natural resources of the region to support his efforts to reach the Pole. Inughuit established three additional base camps in the interior – one on the north side of Lake Hazen, one to the east, and the other on the south side of the lake.

Each of these camps probably featured a kangmah, or Inughuit semi-subterranean stone and sod dwelling roofed over with muskox skins, and stone-covered meat caches. As in 1900-1901, the Inughuit continued to travel throughout the winter to and from the main base camp – now relocated to Cape Sheridan – and the interior.

During the four months of continuous winter darkness, they relied upon moonlight for both hunting and trans-shipping meat and skins, while spending the majority of time in the interior in harsh winter conditions.

Following the Peary era, Inughuit continued to visit the far northern region of the High Arctic, often as guides for subsequent expeditions.

Muskox being corralled by Inughuit dogs.

Muskox being corralled by Inughuit dogs.

Inughuit hunters also reportedly continued to travel to Ellesmere and other islands of the Canadian High Arctic on their own, often in search of muskox skins and meat on the land masses, as well as marine mammals off the east central coast of the island.

According to the Danish Greenlander Knud Rasmussen, these excursions often took place in the spring when sledge travel was still viable before the summer breakup of ice made travel across Smith Sound from Greenland to Ellesmere Island difficult. These parties often traveled along the ice of Kane Basin towards the north, a route they had often travelled with Peary, and occasionally they reached Fort Conger.

As well, the establishment of Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachments at Craig Harbour and Bache Peninsula of Ellesmere Island’s southern and central coasts in the 1920s and 1930s brought Inuit, primarily Inughuit, special constables and their families back to Ellesmere Island for extended periods.

Again, their traditional knowledge and rapid assimilation of new knowledge about the areas they travelled on patrol or while hunting demonstrated remarkable cultural adaptability.

The indigenous occupation of Ellesmere Island changed significantly in 1953. The Canadian government re-established their Craig Harbour detachment, and began the relocation of Inuit from northern Quebec and Baffin Island.

Although they endured many hardships, these Inuit developed an extensive range of natural resource use oriented to seasonal migrations and locations of land and sea mammals and birds.

More than 60 years after the relocation of Canadian Inuit to Ellesmere Island, Grise Fiord, now a community of about 160 people on the island’s southern coast, continues its successful reliance on hunting and the region’s natural resources, having overcome the many challenges they faced during their first few winters in the 1950’s. Inuit continue to live by the ingenuity, adaptability and resourcefulness that enabled their ancestors to inhabit this most challenging of regions.