Sewing Game

Learn how to Play with this Interactive Exhibit

What Not to Wear in the Arctic: The Adaptive Significance of Traditional Inuit/Inughuit Clothing.

Dressing for the weather is something that many people still have a hard time with. Walk by any high school during the cold winter months, and you will likely see groups of shivering, toque-less teenagers wearing only light jackets and running shoes. The clothing used by British and American Arctic and Antarctic Expeditions is the 19th century equivalent of this type of behaviour. Many arrived on the icy shores of northern coastlines sporting clothes made from wool, flannel, broadcloth and leather. Very quickly, explorers realized that these materials were entirely unsuited to polar environments. Tightfitting shirts, pants, gloves and boots restricted movement, not to mention blood flow to extremities like fingers and toes. Likewise, wearing layers of woolen and cotton clothing while engaging in strenuous physical activities like sledge hauling, often resulted in overheating. Woolen garments wet with perspiration were notoriously difficult to dry. Damp clothing would often freeze overnight into a kind of “suit of armor” which the wearer would struggle into at the start of every day. Hypothermia can result under such circumstances, often leading to death.

In contrast, the skin and fur clothing worn by Inuit and Eskimo groups in the North American Arctic and Greenland represented elegant solutions to dealing with extreme cold. Local materials like hide, fur, grass, feathers, and gut were fully exploited by indigenous arctic peoples because of their durability, breathability, waterproofness, and insulation. When combined with complex stitches and extremely functional designs, they were used to produce clothing that was ideally suited to a hostile arctic environment.

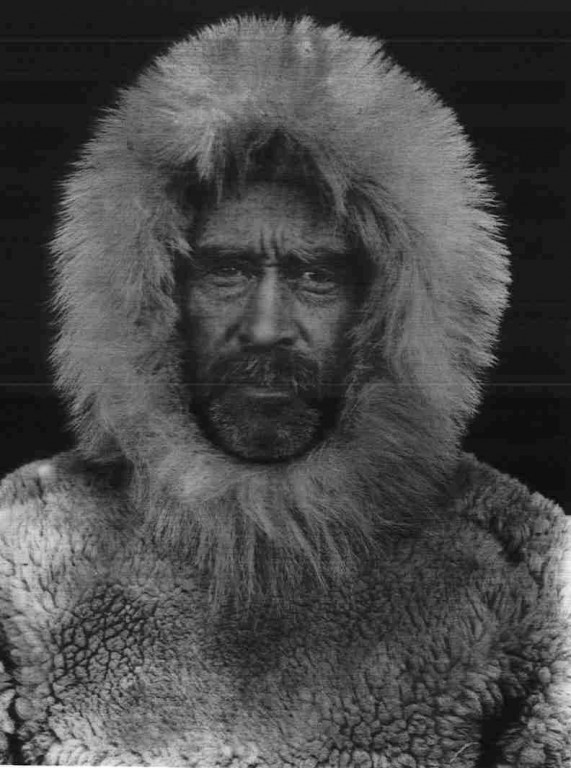

Member of the British Arctic Expedition (1875-76) wearing standard issue wool and cotton clothing.

Member of the British Arctic Expedition (1875-76) wearing standard issue wool and cotton clothing.

Whalers, explorers, and missionaries eventually recognized that using indigenous clothing was the key to successfully living in the Arctic. In 1898, Dr. William Wakeham commented that deaths among European whalers on Baffin Island had been dramatically reduced through the use of what he referred to as “native clothing.” Eventually, explorers also began adopting indigenous clothing. During the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913-1918, Diamond Jenness and Vilhjalmur Stefansson both relied on Inuit dress during their travels through the western Arctic.

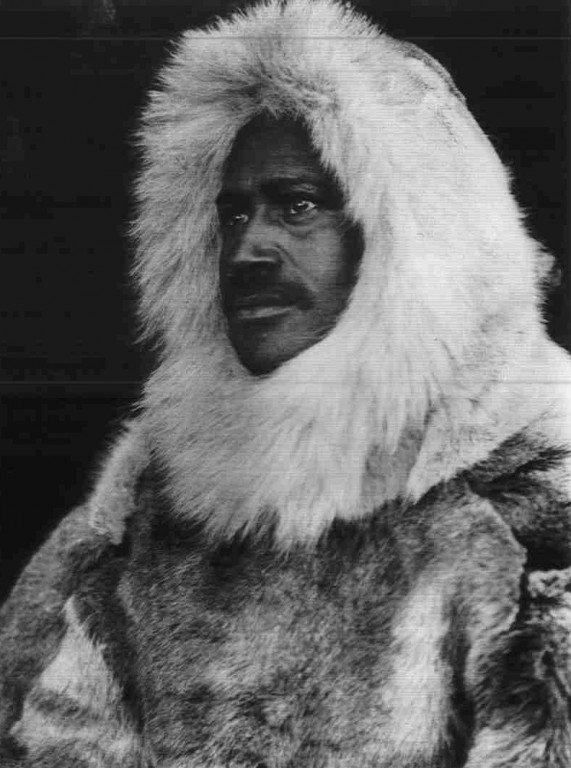

Likewise, Robert Peary astutely determined that the well-made, warm and waterproof skin clothing and footwear sewn by Inughuit women was vital to existence in the Arctic climate. However, the specialized and highly complex skills required producing and maintaining such clothing necessitated that entire Inughuit families travel with Peary. Severe psychological stress caused by long separations of family members and comrades, strenuous and perilous sledging trips, sexual harassment and abuse of women, and compulsory work routines, noise curfews and rationing, was the unfortunate outcome.

American Polar Explorers Robert Peary and Matthew Henson wearing traditional Inughuit clothing.

Why was Inuit clothing far superior to apparel used by Europeans in the Arctic?

Materials

The manufacturers of today’s high-end outdoor clothing lines are constantly developing new types of insulation that reduce the weight of the garment, while at the same time improving its thermal efficiency. Membranes are also applied to the outer surfaces of jackets and pants that render them both waterproof and breathable. Most of these materials are synthetics made using non-renewable petroleum derivatives.

When it comes to waterproofness and insulation, you might be surprised to learn that many natural materials like hide, fur, and gut are equivalent and sometimes even superior to these industrial synthetics. These materials were derived from the land and sea by indigenous arctic peoples for thousands of years.

Skin, Fur and Intestine

Animals like caribou, polar bears, seals, wolverines, foxes, and hares served as important sources of food and raw material to Inuit and Eskimo groups. Large grazing herbivores like caribou and muskox were especially important, as were some marine mammals such as seals. The hides of these animals were eagerly sought after because they satisfied both the aesthetic and functional demands of Inuit clothing makers. From an aesthetic perspective, the coloration and condition of caribou hides can vary based on the time of the year. The black and deep brown hides of the spring and early summer molt are replaced by cream and grey coloring in the winter. The cream coloration of the throat, as well as the white appearance of the belly, flank and tail was used by Inuit seamstresses in ways that made garments attractive.

The thermal efficiency of caribou hide is revealed in its unique structural composition. Long, coarse hairs cover short dense hairs that are fine and soft. Each of these guard hairs has a mesh-like core that surrounds dead air spaces. In fact, the bulky appearance of caribou hide clothing is due largely to the air that is trapped within the hide. When worn next to the skin, these dead air pockets are heated by body temperature. This is the reason why caribou hide is such a great insulator.

Polar bear hides are also excellent insulators. Like caribou, the skin of a polar bear has an outer coat of guard hairs with a dense mass of shorter hairs lying directly underneath. The central core of the guard hair shaft traps dead air spaces, creating an effective form of insulation. Polar bears also have a second secret weapon in the war against cold. The colour of polar bear hair acts as a natural collector of heat. The core of each guard hair traps UV light and conducts radiation to the black colored surface of the polar bear’s skin. The unique insulation characteristics of these guard hairs are found on animals such as dogs, wolves, and wolverines. Keratinous materials like hair also efficiently wick moisture away from the surface of the skin, keeping the wearer dry and therefore warm.

Caribou and polar bear hides make excellent clothing for winter, when temperatures can be as low as minus 40 – 60 degrees Celsius with wind chill. But what about the warmer summer months, when rain and sleet can cause issues? Many Inuit and Eskimo groups used sealskin to make parkas for warmer periods because it was relatively lighter than other skins and hides, and has excellent water repellency. In fact, sealskins are so repellant that they were also used as coverings for watercraft such as kayaks. Furthermore, sealskins are porous and therefore breathable, making them excellent garments for high-energy activities like hunting where sweat and perspiration often result. Even the intestines of sea mammals like seals were used to produce delicate, yet extremely waterproof jackets that were worn over top of existing layers.

Other marine mammals also served as sources of raw material in clothing manufacture, including walrus and beluga whale. Although beluga whale skin was of limited use for clothing, several Inuit groups made the soles of their boots from it.

Some Inuit Elders claim that bird skins are actually warmer than caribou hide, and were therefore used to make coats and trousers with feathers on the inside or outside. Duck skins were prized as boot insulation, as was the down collected from eider duck nests.

Bone, Ivory, Sinew, Antler

Mary Avalak shaving the hair from sealskin to prepare the skin for boot soles

Mary Avalak shaving the hair from sealskin to prepare the skin for boot soles

Manufacturing clothing required a variety of specialized tools, including needles, thimbles, awls, and knives. Thread and cordage were also necessary for sewing. All of these essential items were produced from terrestrial and marine animals.

As we will see, preparing hides was a long and laborious process. Tissue, fat, and meat were removed from the hide using blunt- edged scrapers, some of which were manufactured from caribou long bones. Needles were made from mammal bone, as well as sea mammal ivory. Needles were delicate and easily lost, so they were often stored in ornate cases fashioned from hollow bird bone. The incised decorations on many of these cases sometimes matched the facial tattoos of women. Archaeologist Moreau Maxwell describes finding a needle case at an archaeological site, which even contained the teething marks of a young child. Needles were placed into a strap and tucked into these containers for safekeeping. Among the Paatlirmiut Inuit of the Kivalliq District, needles were stuck into moss pincushions, and kept in small hide pouches that were worn around the neck.

The dorsal tendons from caribou provided sinew for sewing. Sinew had a number of advantages for manufacturing skin clothing. The smoothness of sinew prevented the skin from tearing as it was passed through the hide. Sinew also swells when wet, thereby sealing the hole made by the awl and needle. Antler also served a useful purpose, and was often worked into awls for piercing hide.

Preparing Skins and other materials

Mary Kilaodluk dries a fleshed wolverine hide to use as parka trim

Mary Kilaodluk dries a fleshed wolverine hide to use as parka trim

Unlike synthetic materials, skin, fur, intestine, and whale skin are highly susceptible to decay through bacteria. It is therefore necessary to properly prepare these materials prior to sewing them into garments, as well as adequately maintain them once they are in use. Both require special skills and are highly labour intensive. Ethnographic observations of Inuit women preparing caribou skins indicate that it can take up to 10 hours to repeatedly wash and scrape a single hide of connective tissue, fat, and meat. Drying and softening the hides for clothing an entire family further increases preparation time to about 300 hours of work. Skin preparation had to be done quickly, so that women could sew the clothing necessary to carry the family through the long, cold arctic winter.

Caribou hide preparation begins with blunt-edge scrapers, which were used to remove tissue, fat, and meat from the hide. Scraping crushes the fibres so that the skin does not crack or shrink. The skin was then moistened and left for a day or two, and then scraped a second time using a sharper tool like an ulu; a crescent- shaped woman’s knife found across the North American Arctic and Greenland. Sealskins were much more difficult to process. Oil, blood and salt water must be removed from these skins, requiring repeated washings in fresh water. Sealskins were then staked off using pegs that were knocked into the ground, or stretched on frames. The tension on each tie-off point needed to be individually adjusted, so that the skin would dry evenly. Skins were sometimes left out in the cold for “freeze drying” during the winter months.

Once dried, hides had to be softened in order to make them supple enough to sew and comfortable enough to wear. Softening was done by folding, stamping, crumpling and chewing the hide. Chewing was especially effective because human saliva has emulsifiers that soften skin by breaking down fat and connective tissue. A skin could be made waterproof by removing the hair through submersion in boiling water, or it could be shaved off with an ulu.

Sea mammal intestines were washed and cleaned, following their removal from the carcass. With one end tied off, the intestines were next inflated and hung to dry. Once dry, they were cut longitudinally into long, narrow strips so that they could be sewn into garments.

Measuring, Marking, Cutting, and Sewing.

Sewing durable and waterproof clothing requires the proper sizing of hide pieces and the use of complex and intricate measurement, cutting and stitching techniques. Women using hand, string and eye measurements sized up individuals for their garments. The space between the thumb and index finger, and the spaces between finger and thumb joints were used in place of standardized units like inches and centimeters to take measurements. Skins were then marked down the middle by biting or pinching, and carefully cut using an ulu so that edges were kept straight and pieces could be sewn properly.

Traditionally, the ulu, or woman’s knife, was an elliptical ground stone blade set into a large slotted piece of wood or bone. Ulu handles from the earliest Thule archaeological sites in Canada and Alaska have these types of handles. However, through time the shape and size of ulu handles change, with later forms containing large central holes (finger holes). The familiar “t” shaped handle with rivet holes appears with the arrival of iron from Norse and meteoritic sources.

Strands of caribou sinew are separated into sewing thread

Strands of caribou sinew are separated into sewing thread

Prior to cutting, the seamstress needed to pay special attention to the direction that the fur is flowing on the hide. In order to make the garment comfortable and easy to slip on, the flow was usually from top to bottom. The amauti (also called amaut or amautik) was one exception to this rule. The amauti was a parka worn by Inuit women of the eastern Canadian Arctic. The garment is distinctive for its large hood, which served as a carrying “pouch” for a baby up to two years of age. The garment allowed the child to be carried on the mothers back, thereby freeing her hands and arms for other activities. If the child required attention, the amauti could be reversed so that the baby faced the mother. In addition to protecting infants from frostbite and cold, the amauti was instrumental in developing close emotional bonds between mother and child. In the amauti, the flow of fur inside is reversed in order to prevent the garment from riding up. Inside the baby’s pouch, however, the fur is oriented down in order to reduce irritation.

Functional Advantages of Indigenous Clothing in the Arctic.

Inuit women produced a wide range of clothes for themselves and their families. In addition to the amauti, these included a variety of parkas and trousers, undergarments, waterproof outer layers, socks, gloves, and boots. All of this clothing was specifically designed to preserve heat, eliminate humidity, control temperature, repel or prevent water and moisture from entering, and above all, be durable.

Mary Avalak putting finishing touches on an apkuamiut dance costume

Mary Avalak putting finishing touches on an apkuamiut dance costume

The key to functional arctic clothing lies in its ability to create a comfortable microclimate between the body and the garment. Regulating heat and humidity are critically important. Heat rises within any garment, so Inuit clothing is designed to prevent body heat from escaping. Jackets and pants have few openings, with hoods and narrow neck enclosures fitted with draw strings. Ruffs of fur were sewn around the openings of hoods and sleeves to minimize air from escaping. Inuit seamstresses would use the long and uneven fur from wolves and wolverines for such purposes, as they create eddies around the face that reduces the effects of wind. Garments were also loose fitting so as to trap warm air and not restrict movement. Wide shoulders allow a person to pull their arms out of their sleeves and into the chest area for extra warmth. The famous Canadian Arctic Explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson relates one story about an Inuit woman who became lost during a storm. By simply pulling her arms into her parka and pulling up her hood, the woman was able to sit with her back to the wind and weather out the storm. She returned the next day, and no one thought anything of it, other than to say she should have built a snow house.

Fur is also an effective tool for regulating moisture and humidity. Unlike wool, fur does not trap or absorb moisture. Instead, hoar frost forms on the surface where it is easily shaken or beaten off. Wool garments, on the other hand, can easily become moist and wet – especially if the wearer is engaged in strenuous activities. Explorers often failed to realize the importance of regulating moisture and humidity, and would put on another woolen layer if they became cold. As these garments became increasingly wetter, they also became practically impossible to dry.

Maintenance of Clothing

In order to maximize durability, the number of seams on Inuit garments were minimized and placed in locations where they would be subjected to minimal wear and tear. Regardless, splits and tears were inevitable and needed to be repaired immediately in order to ensure the longevity of the garment. Consequently, a repair kit consisting of needle and sinew was an essential item for hunters to carry. Stains caused by blood and grease had to be removed quickly, so they did not break down the hide. Rubbing the affected area with snow, letting it freeze, and then beating it was done to remove such stains. Hide clothing must be dried slowly and frost beaten off the garment, so snow beaters and drying racks were essential items in any household. When not in use, skin clothing needed to be stored in a cold, dry place. Several sets of clothing were made seasonally for each family member, as most were worn out after a year of heavy use. Old clothing was often recycled in different ways. For example, worn winter clothing might be repurposed for use in the spring or summer, used as bedding, or given away to those less fortunate.

The Use of Traditional Inuit Clothing at Fort Conger

Given the adaptive advantages of indigenous arctic clothing, why did members of the British Arctic Expedition and the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition not make greater use of it? The answers may lie in the fact that producing and maintaining traditional clothing required great skill that was accumulated over many years. American Polar Explorer Robert Peary used traditional clothing almost exclusively at Fort Conger. Doing so required that he bring entire Inughuit families to the site, so that all of the necessary clothing could be produced and properly maintained. This was something that neither of the two earlier expeditions at Fort Conger would have considered feasible, given the strict code of military ethos and values that they operated under. The second reason may have to do with the imperialist attitudes of 19th century Euro-North Americans. The perception that Euro-North Americans were intellectually and technologically superior to indigenous cultures perpetuated the continued use of their existing technology - including clothing. While Peary was very much a product of imperialism, he was also a pragmatist and recognized that adopting indigenous technology would dramatically increase his chances of success in his endeavors.