Botanical Game

Learn how to Play with this Interactive Exhibit

Why collect plants?

Northern explorers had the unique opportunity to observe plants living under harsh arctic conditions. As scientists, they recorded observations of plant structure, blooming and fruiting times, location, soil, and elevation. They collected specimens to document and share their observations with scientists at home. Their notes and collections were very much valued by museums and scientists interested in the distribution of plants worldwide, the composition of plant communities, their potential medicinal value, as well as, the discovery of new species.

By the 19th century, a system for classifying plants and naming them as genera and species had been well-established. Plant specimens were placed into groups of three species by the shape, size, colour and number of parts of their flowers, fruits, seeds, roots and leaves. Species with similar characteristics were given the same generic name and similar genera were placed into the same family. With the development of genetics and molecular biology, additional characters have become available for classifying plants today. Emphasis is placed on analyzing evolutionary relationships among groups of plants. Species that are more closely related to each other than they are to other species are placed within the same genus.

Ecological Setting

Ellesmere Island is the largest and northernmost of the Queen Elizabeth Islands (between latitudes 76 and 83). The island encompasses about 200,000 square km and is about 500 by 800 km in shape. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north and separated from Greenland to the west by the Nares Strait. The island has large glaciers, ice fields, lakes, fiords and mountains. For example, Barbeau Peak sits at an elevation 2,616 meters above sea level. A traditional Inuit name for the island is “Umingma nuna”, the land of muskoxen.

Much of Ellesmere Island is cold and dry with poor soil and marginal or suboptimal habitat (polar deserts). No trees are known to exist.

However, slightly warmer and wetter areas support several dwarf vegetation communities dominated by species such as:

- rush (Luzula)

- avens (Dryas)

- heathers (Cassiope)

- saxifrages (Saxifraga)

- dwarf willows (Salix)

- cottongrass (Eriophorum)

- edges (Carex)

- grasses

- Mosses

- lichens

Food plants are limited to:

- Rhodiola rosea (stonecrop)

- Oxyria digynia (mountain sorrel)

- Cochlearia groenlandica and C. fenestrata (scurvy-grass)

- Pedicularis lanata (lousewort).

Earlier explorers to Ellesmere Island

The first recorded European sighting of Ellesmere Island was by William Baffin and Robert Bylot in 1616 from their ship HMS Discovery. While other Euro-North American explorers explored the same region, it appears that in 1854 Dr. Isaac Israel Hayes was the first non-native American to investigate the island. He took a short excursion onto the shore of Ellesmere Island from the ship Advance, as part of an expedition led by Dr. Elisha Kent Kane in search of the lost Franklin Expedition. Returning later in the schooner United States, Dr. Hayes made the first collection of plants from the island in 1861; reportedly 120 species of vascular and non-vascular plants were collected from Greenland and Ellesmere Islands in that time.

Greely’s plant explorers and collections

During the three years of the Greely-led scientific expedition (1881-1884), the vicinity of Fort Conger was surveyed and samples of plants, birds, rock, fossils and Inuit artefacts were collected. Dr. Pavy served as the naturalist on the expedition, until he was removed following a disagreement upon which Greely relieved him of his post. Lieutenant James Booth Lockwood took over the role of naturalist at that point. Besides Dr. Pavy, records suggest that several other team members collected plants, lichens and mosses including Greely, Sergeant Ralston, Sergeant Elison, Sergeant Cross and Second Lieutenant Kislingbury. Sergeant Brainard found fossil trees, “over a foot in diameter,…, at an elevation of some 800 ft on Judge Daly Peninsula, several miles south of Cape Baird.”

During their desperate retreat south, Lockwood was in charge of the plant specimens that had been collected. This official collection of plants was packed in a tin box and made water-tight by soldering. Other collections of plants were packed in barrels and boxes and left on site at Fort Conger to be picked up at some later date. An inventory of plants observed during the expedition suggests that most of the species were not identified in the field. Following the safe return of the collections to the United States, botanical experts were subsequently able to identify many sets of plants.

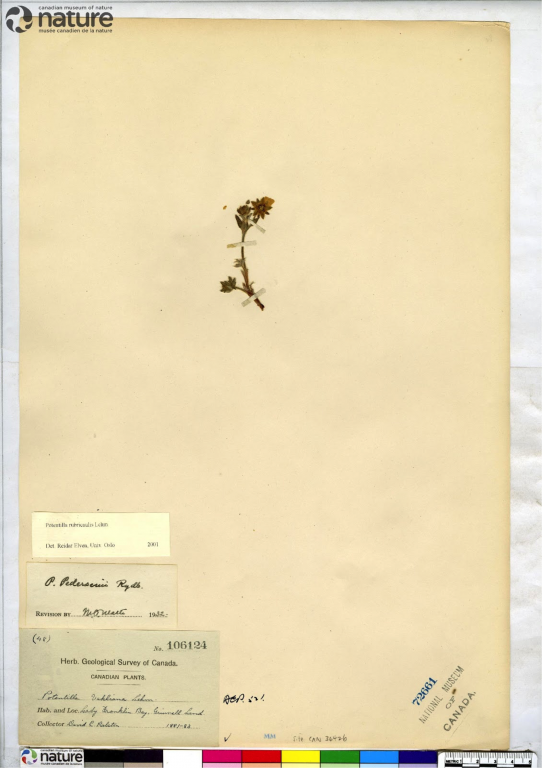

Specimen collections then and now

Plants collected during Greely’s expedition were either preserved in alcohol or pressed and dried. Some of these collections survive to this day in herbaria (museums of plant specimens) in the United States and Canada and at the Explorer’s Club (NYC). The locations of other collections from the expedition remain unknown. Notes that were recorded by Greely’s team were not consistent in detail among the specimens collected. Often the height of the specimen, sometimes the elevation of the site and occasionally, the colour of the flower or the soil type was recorded. Today, many more details are usually noted; date, plant description, associated species, location and ecological setting are often included in the specimen’s label.

Examples of plant specimens collected during the Greely expedition can be found at the Explorers Club in New York City, the Canadian Museum of Nature Herbarium and the Carnegie Museum Herbarium.